A Narrative by Gisu (pseudonym), Nimrokh Journalist.

I took a deep breath; my eyes could not bear to watch my beautiful hair being cut. The cold metal scissors sank into my locks, and with the hairdresser’s merciless motion, they cut through. I felt the weight of the severed hair on my shoulders and simultaneously thought about my sorrows that were supposed to fall away with that hair. Then, with a light head and a feeling of calm mixed with regret, I walked the snowy path home.

I always cut my hair to get through difficult days, because my hair weighs heavier on my neck than my thoughts. At the end of November, my work contract came to an end. This ending coincided with several other unfortunate events in the family that troubled me even more. On one hand, economic pressure and the resulting psychological strain, ever-increasing restrictions, and the lack of work opportunities had added to my constant worries. Likewise, the thought of drifting away from my profession and duty as an independent journalist had made life even more bitter for me.

Yes, this is what my life as an independent woman journalist in Afghanistan looks like: after a pause, a deep breath, and sometimes after several days of self-torment and stress, I decide to start again. I think of those who, during interviews, try to recount what they have lived and experienced as Afghan women—to create a narrative of struggle, resistance, and standing firm against restrictions for the next generation, and in a way, to prevent its repetition. On the other hand, the only hope for the preservation of these narratives and stories lies with independent media and journalists who, despite facing all the challenges, continue to work to keep the voice of resilience alive.

Just two days ago, a nurse from Uruzgan wrote to me that a girl had become a victim of domestic violence, was injured, needed help, and that we must raise her voice. But shortly after, she messaged again saying that the girl’s life might be endangered again after the news is published. I am caught in the dilemma of writing about this violence versus staying silent to prevent the situation from worsening for the victim—and even now, as I recount this incident, it troubles and torments me.

Over the past four years, I have written about the experiences and narratives of many women—from victims of domestic violence to women and girls who were imprisoned and tortured for protesting against Taliban group policies or for various pretexts, including “not wearing mandatory hijab.”

During these four years, gathering information and protecting sources and victims amid ever-tightening restrictions on free journalists has always been one of the challenges I have faced. Or when I would leave home to prepare reports and interview victims, passing through Taliban checkpoints was like a terrifying nightly nightmare that still has not released me. Over the past four years, we have seen how Taliban fighters, by violating privacy, inspect the mobile phones of citizens—and in many cases, of women and girls—in the streets and alleyways of Kabul, and in some cases, conduct physical searches. Through this, they identify opponents, protesters, independent journalists, and civil activists. I too, as a journalist, went through this terrifying experience, which dragged me to a Taliban station. Fortunately, I was saved through the intervention of my husband and brother.

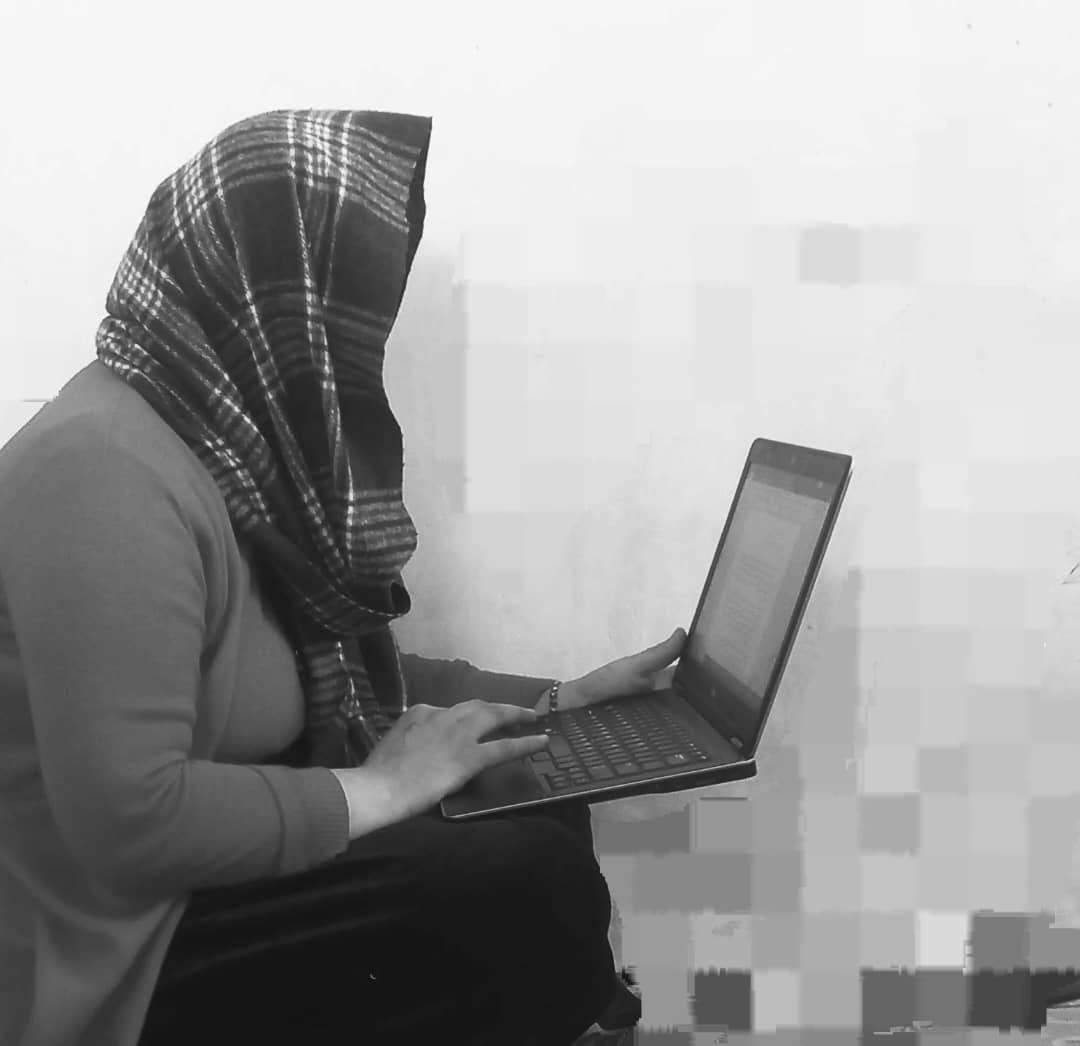

I always dreamed of fulfilling my responsibility as a journalist in the face of injustice and discrimination, and being a teller of truths that would be effective in improving society’s conditions and achieving freedom, so that my family and friends would be proud of me. But over the past four years, my colleagues and I, as independent journalists, have been forced to work anonymously and live in the shadows. Under Taliban rule, speaking the truth and recounting what happens to us women and girls under Taliban governance in Afghanistan is considered “propaganda against the system” and “collaboration with foreigners” and has been criminalized. This is how speaking the truth, narrating the oppression and systematic violence of this group, is covered up and suppressed with the label of “propaganda against the system.” Journalists languishing in Taliban prisons with no news of their fate are a clear example of this repression.

A while ago, I heard the story of a journalist’s torture from his family. They said the Taliban, to extract a forced confession, had hung the journalist upside down by his feet and suffocated him with plastic. This is how they forced him to say he had propagandized against the Taliban regime. After the torture, they made him pledge never to work as a journalist with any media outlet again. Of course, this is only one side of what the Taliban does to journalists. On the other side—and the worst part—is that media outlets also abandon journalists and their families in such circumstances, making journalists’ lives even harder than before.

As an independent woman journalist, I don’t want the world to remember only the statistics. I want them to remember the names, voices, and fears hidden behind every piece of news published from Afghanistan. I want to say that the price of writing in Afghanistan under Taliban rule is not merely professional deprivation—it is the cost of living in constant fear, forgetting one’s name, hiding one’s voice, and accepting life in the shadows. But we know that this very act of writing and creating narratives is the only thing preventing the Taliban’s oppression from becoming normalized.

I also want to say: as long as even one woman in this land is forced into silence, as long as cut hair remains a symbol of mourning and protest, I too will not put down my pen. Journalism for me is not a profession—it is a form of resistance, an effort to preserve collective memory against the forced forgetting imposed by the Taliban. Perhaps I cannot change the world, but I can refuse to let what has happened to us be buried nameless and voiceless. Until freedom comes, I will narrate.