We, the women of Afghanistan, from the day the Taliban entered Kabul, experienced one by one things that we could not even imagine. In the early days, I thought that in a world where everyone claims to defend human rights, the Taliban could not overbear Afghanistan with their primitive, fossilized mindset. But that thought did not last long. It was enough for the leaders of this group to enter the cities, climb onto the pulpits, and by reciting a few verses and hadiths, eliminate women from society—while, on the other side, the world, with all its human rights slogans, turned a blind eye and a deaf ear overnight, leaving Afghanistan’s women alone in complete darkness.

During these four years, I have read in the media the stories of many women’s lives, and I found myself in every single one of their words; I choked up, I cried. Yet I could not recount what I had gone through myself. This choke was stuck in my throat for four whole years. Now I want to share part of it here—to record the suffering of an Afghan woman in the twenty-first century in history.

The First Year

During the Republic, I was a bank employee, and four months after the Taliban came to power, one afternoon, I and three other women were told not to return to the office from the following day. One of my colleagues said that a Taliban member had introduced four people who must be hired and had also stated that female employees must be dismissed. I, a mother of two children who covered a large part of my family’s living expenses, found myself, on top of all the other restrictions, caught in a new kind of misery. After that, I was unemployed for a while, and following much effort, I managed to get employed in the “Information and Reception” section of a language institute. For me, unemployment—alongside poverty and hunger—felt like solitary confinement in a prison, within a bigger prison that was Afghanistan under Taliban rule.

I worked at this institute for nearly eight months, until yet another dark afternoon, when several members of the Taliban’s Ministry for the Promotion of Virtue and Prevention of Vice entered the institute’s office. It was when some of the male teachers had just finished their classes and had come to drink a glass of tea. When the Taliban members entered, I and another woman, who was a teacher, were also sitting there. One of the Taliban members, dressed in white and holding a walkie talkie, without saying anything else, gestured for me and the other woman to leave. When I asked why, his face grew angrier, saying: “You two unveiled Siyasars[1], what are you doing among all these men?”

One of the male teachers, unable to tolerate such idiocy, said: “This is an institute, and these women are teachers here.” Upon hearing this, the Talib told us to stand up, then started slapping and beating the male teacher. After a while, with apologies and pleas, we managed to pull our colleague away from under the blows. In the end, he told me and the other woman: “You no longer have the right to come here and to be among all these non-Mahram men who have no knowledge of religion and Sharia.”

When we left the institute, I saw them going into the classrooms. The next day I went back again, because I could not stop working. After I lost my previous job, my family’s situation had become critical, and my husband—who was unable to provide for us—would start disputes under various pretexts. The story of domestic violence, which intensified in the second year after the Taliban’s takeover, I will write about later.

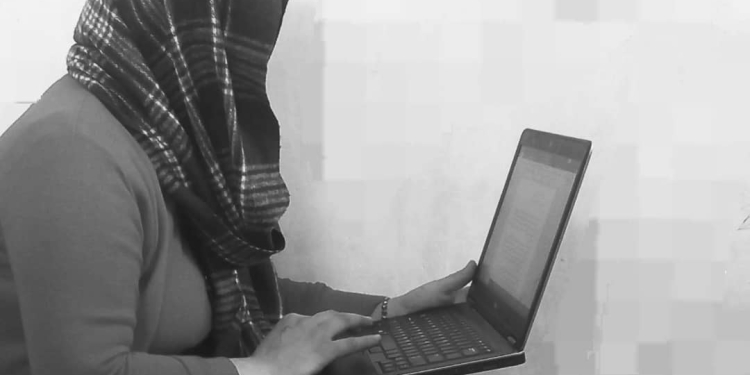

The next day, when I entered the office, the institute’s director laughed and said: “It seems that the Taliban and [the Ministry for] the Promotion of Virtue are just hot air for you.” I replied: “I cannot bear hunger and the Taliban’s fear at the same time. I work, and this is my protest against this fatuous group.”

The day before, the Taliban’s virtue-enforcing had not only insulted and expelled me and my colleague from the institute, but they had also forced several female students out of classrooms for the crime of not observing the Taliban’s version of hijab. They had also threatened the institute administration that if unveiled girls were found inside the classrooms, they would shut down the institute.

One week later, those virtue-enforcing returned. This time, they forced me to go to the police station with them and told me to call my husband. When I called him and he arrived, one of the Taliban members—who spoke the Hazaragi dialect fluently—said to my husband: “Your wife sits in the office among non-Mahram men without a veil, showing her chest and hips to arouse them, and in this way she brings you money. And you are zealless, happy about it, and you call yourself a man.”

The Second Year

From the day the Taliban’s virtue-enforcing forces took me to the police station for the “crime” of working, and made my husband sign a pledge not to allow me to work outside the home, I realized that no Afghanistani man—when he feels himself in danger—will support any woman, even if that woman is the one who bears the greatest burden of their shared life. Of course, this is not only my case; I am certain that in the home of every Afghanistani man, at least one girl or woman has been harmed by the Taliban’s decrees, but none of these men raised their voice. Yet for me, it was not only silence.

About six months passed since I became unemployed again, and my husband grew more violent each day. “You made me ashamed at the police station,” he would say. I was astonished at how someone could change so much overnight. A man who, during the Republic, was himself an employee and saw women working alongside men, even alongside himself in offices—and nothing ever happened that could be considered contrary to Sharia or Islam—was now saying this to me, his wife, the mother of his two children.

The Third Year

Another year passed with an avalanche of hardships. During this year, I was repeatedly and brutally beaten to the point that I could no longer defend myself, and there was no one to stop it. There was no institution or organization to which I could turn to defend myself, and there still is none. Of course I endured it — I loved my life because I had worked to build it. But what happens in a patriarchal system is, ultimately, the erasure of women beneath male domination, and I too was being crushed in that grinding press.

I could hardly decide to separate from my husband, but what frightened me most was the thought that I might be unable to stay with my children. This feeling forces many women to endure a cycle of violence until it becomes an ordinary part of every woman’s life—but I could not bear that cycle. Custody rights are granted to the father in Islam, and under the Taliban rule, which claims that same Islam and Sharia, I was certain that staying with my children would be the hardest thing. Still, I chose not to endure the violence; yet on many occasions the prospect of being separated from my children nearly made me give up. I kept thinking that if I tolerated this cycle of violence, my daughter would learn from me, and tomorrow if she faces violence she might not have the strength to break this chain.

The Fourth Year

It has now been nearly six months since I separated. When I divorced, I tried hard to take both of my children with me, but I failed. I want to tell you something even more painful here: in the final hours that I was living under a roof I had spent years building, when my brother, my parents-in-law—who have always been kind to me—and I had gathered to talk, an elder from my husband’s family arrived; he happened to be a mullah as well. When the question of custody came up, I relinquished my mahr (dower) and everything I had to my husband so that I could keep them with me. But when that mullah spoke, I understood the true meaning of “Islam” in the lives of women. “The boy, as the father’s bloodline, should remain with his father; and the girl, being destined for others, should be given to her mother,” he suggested.

That statement fell on my skull like a mallet. “In that case, I will not relinquish my mahr, and I will take both my children with me,” I said. I did my utmost. Although my mother-in-law said one should not separate a mother from her children, her words carried no weight, and in the end I was forced to bring only my daughter with me. Now, my son is my whole rue, and I can not do anything for him.

Then, I was forced to migrate. Now, in exile, I feel I have left all of myself in Kabul. The Taliban took my sense of life and my whole existence from me on the very day they humiliated and degraded me for the “crime” of working.

[1] A derogatory term for women, literally meaning “black-headed.”